Collin Brooks

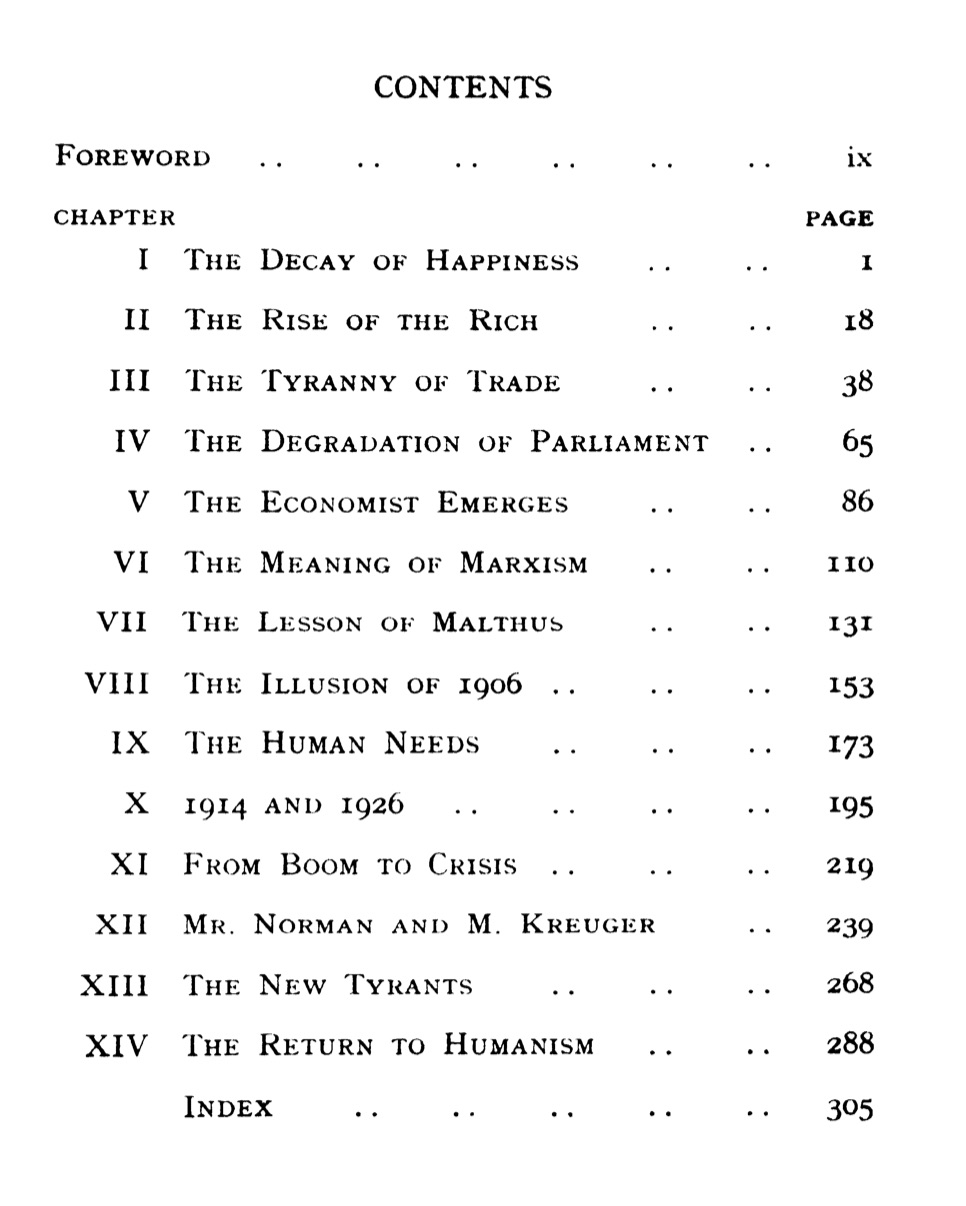

The Economics of Human Happiness (1933)

From the Foreword

There is nothing original in this book. It is, in the best meaning of the term, a commonplace book. If it fails to say for half-a-guinea what a multitude of men are saying in pub and club, tavern and train, for nothing, it will be because I have an impediment in my speech arising from the need for controlling the epithets which they can use freely.

It is agreed on all hands that society is sick, perhaps sick unto death. As the visible representative of society the plain man, the average citizen, is the victim of a malaise which has drawn about him a horde of economic busybodies eager to explain the cause of the seizure and to suggest and administer remedies. This book suggests bu t one remedy, the age-old advice of the onlooker - "give him air". Ignoring the Heath-Robinson-like contraptions of the currency cranks, this book advises the stricken wayfarer to take up his bed and walk. Deriding the nostrums of the rival schools of rejuvenators and the profferers of economic trusses and crutches, it suggests to that smitten traveller to “ get up and work it off It is, however, something different from a course of economic Coueism. It preaches not a faith cure, but a lack-of-faith cure—a cure to be induced by a healthy scepticism about those who have hitherto been the witch doctors of the tribe.

This book, it may be said, is a loose treatise on how to be happy though civilized. It is an expansion of the thought that a " managing " Government is as great an affliction as a " managing " wife into the suspicion that a Planning Body is only a new-fangled name for an old- fangled affliction, a busybody. It is based on the conviction that what is really wanted is not better leadership, more scientific leadership, reformed leadership, dictatorial leadership, democratic leadership, or any other qualified leadership—but less leadership. It enunciates the doctrine that we are suffering not so much from faulty organization as from organization without any adjective whatsoever . It also suggests, with courtesy, as I hope, and in a Pickwickian sense, that in the thieves kitchen of modern "leadership" too many crooks have spoilt our broth.

The book is no manifesto for perfect freedom. It does not clamour for a return to cut-throat competition. It is not a pleasing fable from the Blue Book of the Laissez- fairies. It is only an expression of Individualism inasmuch as i t suggests mildly that the individual should be the starting-point of political thought, and not the trade union, or the joint stock company, or the Empire, or the whimsies of some dead dreamer. We live in the age of George V, not in that of Thomas More, or of Utopia, or even of Oliver Twist. This book derides the idea that we shall at tain happiness by Marxing through Georgia or merely—as Mr. Chesterton might say* and advise—by asking for More.

Individualism is not enough. Social ism is too much. No “ism" is necessary. The individual cannot do every- thing alone ; he must indulge in communal co-operation for common purposes. But the individual does not need a Government Department or a Board of Governing Directors to spend his wages for him ; educate his children for him ; select and vet his mate for him before those children are begotten ; form his habits for him ; arrange his dietary for him ; construct his morals for him ; select and censor his amusements for him ; standardize the commodities of his daily life for him, and arrange his contribution to a burial club for him. He needs a Government which wi l l govern, in the old sense of maintaining law and order and the enforcing of contracts, and which will stand in relation to his life as the policeman theoretically stands in relation to his home—ready at call, but unable to enter without an invitation.

Downloads and Links

- Download The Economics of Human Happiness (1933) by Collin Brooks - PDF (62.2 MB) - 321 pages.

- Read The Economics of Human Happiness (1933) by Collin Brooks on The Internet Archive and download in different formats

- Web search for the book by ISBN:9781245801713

- Web search for the book by author and title